Emotional intelligence

August 06, 2003

By Alexander Anichkin

Giving up the day job to live as a Renaissance man can entail becoming a jack of all trades and master of none

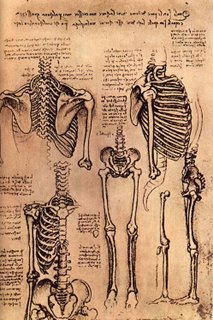

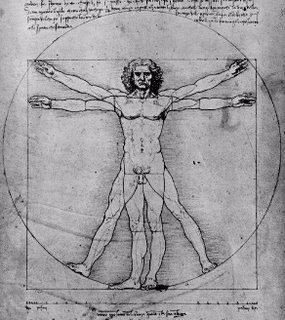

I WAS at school when Soviet television showed an Italian film on the life of Leonardo da Vinci. The entire class was captivated and we all decided that we wanted to be Renaissance men, seeing Leonardo’s legacy not so much in terms of his genius but in his range — his determination to pursue whatever it was that interested him. “Ploughing the earth in the morning, writing poetry in the evening” as Nikolai Nekrasov, the 19th-century poet, once put it.

Five years ago, aged 40 and living in the UK, I started thinking about Leonardo again and, after 20 years of office life, joined the increasing number of disillusioned daily-grinders who, over the past decade, have side-shifted in search of a more fulfilling life.

It is not just the work-life balance, but a rejection of the one-track lives that we are obliged to live in this age of increasing specialisation. As we work longer hours at the day job, who has time to have more than one string to their bow — the research scientist who is also a poet, the novelist and inventor, engineer and musician? What I wanted to find out was, is the Renaissance ideal more fulfilling or even possible in our driven society?

I was inspired, specifically, by a meeting with the English-born artist James Gracie, who is based in France. Gracie threw in his job as a graphic designer in London 17 years ago to create the Renaissance ideal. He roofed, wired and plumbed his French barn conversion because it interested him to do so, painted pictures which sell on the international market, and rekindled his first love — music — by digging out his saxophone and joining a band. He was equally happy discussing the brushstrokes of Gauguin or taking his motorbike to pieces. Interest and creativity in all that you do is the essence of Renaissance man, says Gracie. “I hate the idea of doing things to a set manual, repeating what others have given me without adding my own creativity. I teach English two days a week to pay the bills, but I see this not as going through textbooks and exercises but as a way of showing my students language as a combination of shapes and patterns in the same way that I see objects as an artist.”

Thus encouraged — and spurred on, as was Gracie, by the arrival of children — I left my full-time newspaper job and moved with my English wife to Mid Wales. I was immediately engrossed in building a dry-stone wall to keep the nearby farmer’s sheep out of our orchard, learning by trial and error and by studying the local landscape and talking to craftsmen. I built a wardrobe for the bedroom, borrowed books and learnt plumbing and wiring simply to see if I could do it. Enthused with the thrill of being able to devote myself to whatever interested and excited me at that moment, I never got tired.

Moreover, I was with my family all the time, a role model to my children and object of their love and admiration rather than a grumpy commuter. “Creativity and variety are essential,” agrees Tom Jeffries, who, in his early forties, threw in his job as an accountant, moved to the country and works two days a week as an acupuncturist, two days as an adviser for the Citizens Advice Bureau, and looks after his young children full-time while his wife, a fitness instructor, retrains as a psychiatric nurse. “Life is 100 per cent more fulfilling — intellectually and emotionally,” he says. “But you have to rearrange your priorities at the same time as you adjust your life, and accept that you are not going to get the same financial rewards if you choose to pursue a range of interests instead of one career single-mindedly.”

This is a common theme. Matthew Rea, in his early forties, is a would-be Renaissance man who works four days a week in London as a high-flying City lawyer and commutes to North Wales on Thursday evenings. Guests recently sat down to lunch at a magnificent oak dining table designed and built by Rea.

“I am excited by the idea of learning new skills and knowing that I can do anything that needs doing to the house, from fixing the roof to plumbing,” says Rea, who is also a passionate climber. “But in today’s society you also have to concentrate on one skill above all in order to survive financially.”

However, this is not incompatible with the Renaissance ideal, he says. “I find my work hugely creative and get enormous pleasure from it. If I didn’t I would seriously consider chucking it in and retraining as a plumber.”

Renaissance man, in other words, is not so much a matter of being able to turn your hand semi-successfully to a dozen jobs, but a state of mind: open and receptive rather than bored and cynical. “Exactly,” agrees Rory Nicholl, who left a London auction house after 20 years to set up his own antiques business, run the family farm and indulge his passion for history. “Pursuing what excites you is the key to self-fulfilment. The mind is stimulated constantly, which guards against weariness and negativity — which are the death of the Renaissance ideal.”

Nevertheless, as we prepare to move again, the expression “jack of all trades, master of none” nags at the back of my mind. I look back over the Renaissance experiment with a mixture of weariness, pride and frustration. It has not been a failure: I have worked part-time with a fine-arts dealer to further my interest in paintings, I have continued to write articles and given a satisfying series of lectures on Russian politics; I have learnt Welsh, embarked on an MA, revived a youthful passion for running and completed two London marathons and, occasionally, washed dishes to pay the bills.

But the book is still unwritten, the house still needs repairs and, much like Leonardo, I have not finished anything I set out to do. Should I pursue the dream in our new house, or call it a day and go back to full-time journalism? Is the continuing financial insecurity worth the adventure? Indeed, can Renaissance man truly flourish in our one-track society where “what do you do?” invites a one-word answer, where children specialise by their mid-teens and a rounded education is a thing of the past?

“It doesn’t matter if projects are unfinished or you don’t reach the level of Leonardo,” insists Gracie. “Even he left sketches that others worked on later. I know I can’t paint like Cézanne or play like Coltrane, but it only helps to learn some humility.”

Nevertheless, not only does society insist on defining others by their most impressive skill — Leonardo is remembered for the Mona Lisa rather than as an inventor — but perhaps there is also a nagging desire in the human condition to excel in one area above all others.

Chekhov longed to be a brilliant doctor even while his contemporaries acclaimed him as a playwright. So while I can still look at my stone wall with pride, I shall go back to concentrating on what I do best — writing — and from now on I shall do the plumbing only when I cannot afford to pay the plumber.

This article was first published in the Times (London.)